Slide Rules

The summer has been a lot, but I spent a lot of time watching different math and computer science videos, including this video about ways to optimize square root calculations, along with the incredibly quick inverse square root function used in graphics.

With the whole discussion of bit shifts and logarithms to optimize calculations, I was reminded of past methods of simplifying large calculations with lookup tables, like slide rules. For most people in my generation, calculators are the staple of math-doing; however there were ways before, and the reasoning behind them are crucial in understanding modern methods of approximation.

Logarithms and Log Books

Like how addition and subtraction are opposites, exponents have their inverse: the logarithm. As a quick recap:

\[\text{If } a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}, \text{ and } a^b = c , \text{then} \log_a(c) = b \quad (\text{except when a is 0 or 1, or when c is 0})\]and like how we have the distributive property for addition with multiplication:

\[\text{If } a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}, \text{then } a(b + c) = ab + ac\]we also have the distributive property for multiplication with exponents:

\[\text{If } a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}, \text{then } a^{(b+c)} = a^b \cdot a^c , \text{ or } \log_a(b\cdot c) = \log_a(b) + \log_a(c)\]Notice how given a value $a$, we can turn the equation $b\cdot c$ into its equivalent $a^{\log_a(b\cdot c)} = a^{\log_a(b) + \log_a(c)}$. This means that if you can easily convert numbers between itself and the log of itself, you can easily turn any multiplication into a much simpler addition problem, and through other conversions, you can turn other problems, like taking the log of a number in a different base, into a subtraction problem

By Henry Briggs - http://www.pmonta.com/tables/logarithmorum-chilias-prima/index.html, Public Domain, Link

Above is an example of log book from the 17th century, calculating the base-10 logs of various integers to very high precision, allowing them to be used in calculations that need less precision.

Slide Rules: The Logarithmic Analog Calculator

Slide rules turn the additions and subtractions of the “log-o-fied” calculations into physical movements that also automatically convert the numbers to their logarithmic form and back using a logarithmic scale. you would move the slide rule to compute the equivalent of $\log a + \log b = \log (a \cdot b)$, but with the changed scale of numbers, the user doesn’t need to deal with consulting a log book to convert the numbers to their logarithmic form and back.

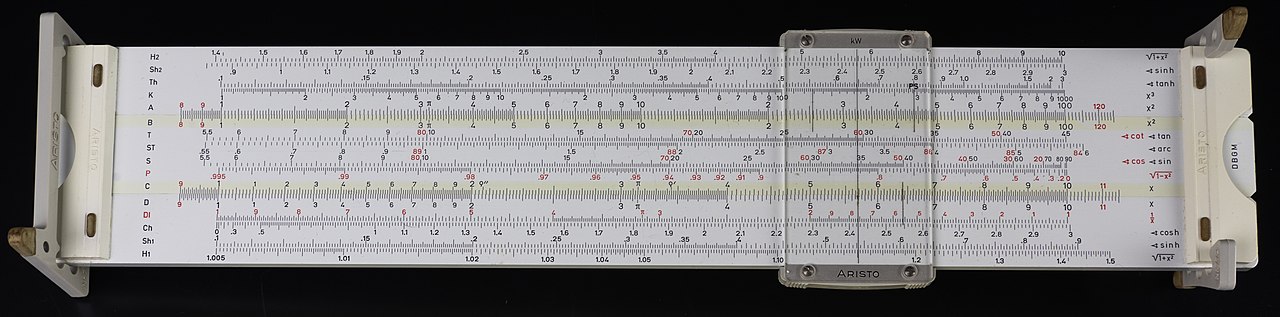

This was often was taken to extraordinary lengths, giving slide rules like this:

which could be use for various calculations, from logarithms to trigonometric functions. More can be found out about the various calculations that can be done with here.

References

This post was heavily inspired by Professor Stewart’s Hoard of Mathematical Treasures by Ian Stewart. I would highly recommend getting all of his “mathematical compilation” style of books, which are all available on Amazon (NOT AFFILIATE, I just love his books).

Images were obtained from Wikipedia.