How Do Models Think, and Why Is There Chinese In My English Responses?

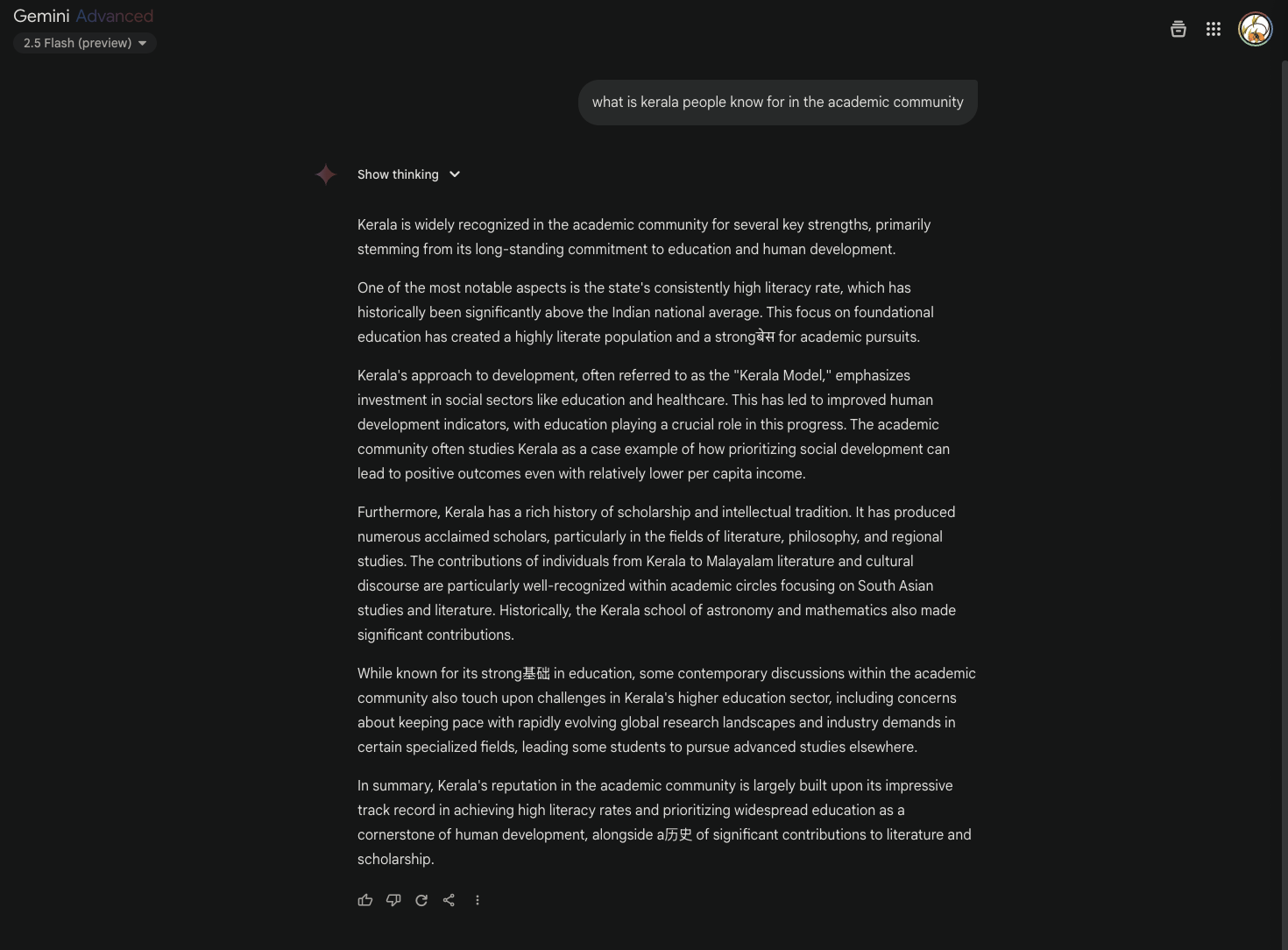

So I was talking to my friends in UCLA’s Game Music Ensemble (check them out here!) about what the different states in India are known for (it was an interesting discussion), and I tried asking Gemini what Kerala is known for:

Now the response looks normal at a glance, but if you read carefully, there are 3 instances where a non-English word is used:

“… highly literate population and a strongबेस for academic pursuits…” (बेस = base, Hindi)

“… While known for its strong基础 in education…” (基础 = foundation, Chinese (simplified according to my roommate))

“…alongside a历史 of significant contributions…” (历史 = history, Chinese (simplified according to my roommate))

The best part is that the words make perfect sense in the context they are in, ONLY if they were translated into English. When I first saw this, I thought, “Oh, this sounds like code-switching.”

What is code-switching?

This isn’t the imposter syndrome version of code switching that you do when you’re in a new environment (it is similar though); in linguistics, code-switching is when someone uses multiple varieties of a language or even distinct languages within the context of one conversation. Though I’m technically monolingual, I do use code-switching in my daily life, from using other languages’ expletives when they feel more appropriate, to reducing the amount of slang I use the moment a proper adult (i.e. my parents) is joining the conversation.

However, code-switching is a very human phenomenon, resulting from situations of high stress, want to express ideas in a more appropriate way, humor, etc. These “omniscient” and “serious” models shouldn’t need to resort to jumps in languages, especially for basic words like “base.” So why does my English question get a few instances of non-English words?

What can Cause Accidental Code Switching in LLMs?

Large Language Models like Gemini are trained on absolutely massive datasets of text and code scraped from the internet. This data is incredibly diverse, encompassing not just clean, grammatically perfect English, but also multilingual content, websites with mixed languages, parallel texts (like translations), forums where users naturally code-switch, and even just poorly formatted or mixed-language documents.

When the model is trained, it learns patterns and relationships between words and concepts across this vast corpus. It builds a complex internal representation of language. While the primary goal is often to generate coherent text in a specific language (like English in this case), the model’s underlying knowledge base is fundamentally multilingual.

Here are a few potential reasons why you might see “accidental” code-switching:

- Training Data Contamination: The most significant factor is likely the nature of the training data. If the model encountered many instances where English text about a topic (like education or history) appeared alongside or in close proximity to its translation in another language (like Hindi or Chinese), it might learn a weak association between the English word and the foreign word. When generating text, it might probabilistically select the foreign word based on this learned association, especially if the context strongly aligns with the concept. Think of it like a very sophisticated form of predicting the next word based on preceding text, but occasionally pulling from related concepts in other languages present in its training history.

- Embeddings and Semantic Proximity: LLMs represent words and concepts as vectors in a high-dimensional space (embeddings). Words with similar meanings, even across different languages, might have relatively close embeddings. For example, the English word “base,” the Hindi word “बेस” (bes), and the Chinese word “基础” (jīchǔ) when used in a conceptual sense like “foundation” or “base for something,” might be located near each other in the model’s internal semantic space. When the model is generating text and the context points strongly to the concept of “base” or “foundation,” its generation process might sometimes drift towards the embeddings of the foreign words that are semantically close.

- Multilingual Pre-training: Many modern large LLMs are pre-trained on a wide variety of languages simultaneously to improve their overall language understanding capabilities. While fine-tuned for English responses, the underlying multilingual architecture means they retain knowledge of other languages. This makes them capable of translating or understanding multilingual prompts, but it also slightly increases the probability of generating non-English tokens unintentionally during standard English generation if the internal weights nudge in that direction.

- Tokenization: LLMs break down text into tokens. Sometimes, common foreign words or phrases might be tokenized in unexpected ways, or tokens might represent sub-word units that are common across languages. While less likely to cause full word substitutions like the examples seen, tokenization schemes can sometimes play a subtle role in multilingual output.

It’s less about the model “thinking” in a human sense or intentionally choosing to code-switch for social reasons. It’s more a byproduct of the statistical patterns and associations it learned from its vast, messy, multilingual training data and the probabilistic nature of its text generation process. The model predicts the most likely next token based on its training, and sometimes, given a specific context and its internal state, a foreign word that appeared frequently in similar contexts in the training data gets selected.

Conclusion

The appearance of non-English words like “बेस”, “基础”, and “历史” in an otherwise English response from a model like Gemini is a fascinating glimpse into the inner workings of large language models. It’s not true human code-switching driven by social or emotional factors. Instead, it highlights the inherently multilingual nature of the massive datasets these models are trained on, and the inherent fact that these LLMs rely on randomness in their text generation process (meaning statistical anomalies like the prompt above are entirely possible).

This phenomenon underscores that while these models can produce incredibly fluent and contextually relevant text, their process is fundamentally different from human cognition. They don’t “know” languages or “choose” to code-switch; they probabilistically generate sequences of tokens based on patterns learned from data. Seeing these linguistic “ghosts” from other languages pop up serves as a reminder of the complex, multilingual tapestry that forms the foundation of their intelligence.

Extra Credit: Using Code-Switching Intentionally

While researching code-switching for this post, I stumbled upon two very interesting papers:

-

This paper goes over trying to make an LLM that can naturally codeswitch, and

-

This paper goes over how to use code-switching in question prompt to illicit unexpected responses from models like ChatGPT.